(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2007)

_________________________

I was watching FW Murnau’s Nosferatu in a cinema a few years ago when something quite unexpected happened. It occured on the first night in Orlok’s castle, just after Hutter has cut himself with the bread knife on the stroke of midnight. Count Orlok extends his arm towards Hutter across the table. All of a sudden, the Count's arm started bubbling and fizzing. It was as if the poison of the vampire’s presence was eating away into the very medium that was depicting him. Though I’m sure whoever owned the print would have been horrified at such a sight, I was thoroughly delighted by such an apposite coincidence of print damage and subject matter (possibly because I had made similar experiments myself with 35mm transparencies many years previously). That’s by the by however, the important point is that it raised in my head a large and generally unexplored area of effect in film, whereby degraded and otherwise abused film stock could be used to heighten certain effects within what the film itself showed. You can imagine my happiness then on finding that Bill Morrison had made a film in exactly this area, Decasia, in which he pieced together what would normally be considered as utterly ruined sections of film stock to create a new film in which the interplay of surface damage with the subjects depicted became part of the film’s overall conception.

I’ve mentioned the happy accident of effect in Nosferatu. Decasia is filled with such images. At one point in his film there is a section of what looks like white-robed dancers of some kind, or even the meeting of a witches’ coven – it is extremely difficult to make out exactly, but that's beside the point. What it could be however, is one of the most atmospheric and mysterious representations of the meeting of the three weird sisters out of Macbeth that I have ever seen, with their ghostly, misty forms being more air than solid matter. These ghostly forms occur frequently throughout the film. Often the film is slowed down to the level of individual frames and so becomes a collection of phantoms, spectres, and ghoulish distorted presences. There is more to unnerve here than in many more traditional representations of ghost stories on screen.

Death imbues its presence throughout the screen. At one point we see standing nuns depicted in negative. This reversal is shocking and, with the line of children they are shepherding pictured advancing towards them, turns them into angels of death counting departed souls instead of anything particularly beneficent. Later, riders on a big wheel at a fairground are subject to a similar sinister operation as an enveloping blackness clouds across the image. The accompanying horn blasts on the soundtrack make it seem as if some deity or other is dispensing random, indifferent fates to the riders – this one, this one, not this one.

This darkness covers the sea too. We see footage shot from the mast of a ship, the film recalling Der Magische Gürtel, the First World War record of a U-Boat’s matter of fact destruction of merchant shipping. That film is shocking because the sinking of ships and goods is so plainly shown. Here, with bow of the ship shown in negative beneath swathes and swatches of damage, it appears as if it could be one of the very merchant ships destroyed, and heading towards its destiny.

This interplay between surface and image throughout maintains constant interest. After the whirling dervish at the commencement of the film (which sets up one of the film’s recurrent visual themes of spinning, turning and spooling) there is then a puff of cloud like an effect in an early Ali Baba film, after which the clouds gradually roll back to reveal the delights on offer. Later, in a shot of waves breaking on rocks, the surface of the film itself bubbles and cockles in liquid ferment. In the final section, as parachutists are pictured falling through the air – which is at the same time an exercise in falling through the uncooperative texture of decaying nitrate film, the film moves into a tracking shot as a black sun glints through the trees on the horizon. he parachutists have established a wartime theme, and suddenly the film itself erupts in shapes reminiscent of WW1 bomb blasts, followed by their spray of dirt.

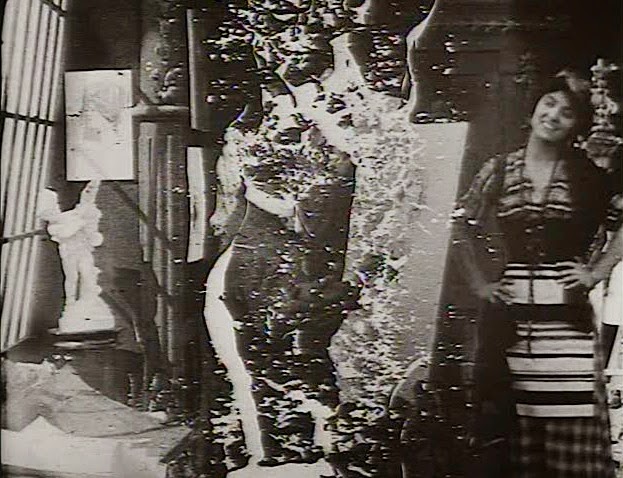

There’s humour here too though, as with the boxer battling with the damage itself (and landing a knockout blow that causes the film to erupt into another scene); the painter in his studio where the damage of the print can stand for either the white heat of creative composition or the fact that he is so perturbed by his model that he is in a stew; and the miners knocking to see if they can hear life below, with the print damage resembling the noise waves that give them hope.

Tthere are some exquisitely lovely images too, such as the shot of people and camels travelling across the horizon, in a scene that calls to mind something similar in Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. The nitrate damage also has its own beauty regardless of interplay with the images it obscures. At times it is like watching a monochrome Stan Brakhage or Norman McLaren film.

In fact, one becomes a connoisseur of damage and patterning watching Decasia, watching the different effects, the filigree and the fronds, the coral and speckle and blotch and smudge, the solarisation and flare, the snakeskin patterning and staining, the wrinkles and buckles, the scratches and the scumbles, tears, blisters and puckers, the bubbling, the bloating and the crimping.

At the end of the film, the dervish is still turning, as if he is spinning his own decay, or even trying to prevent it as long as he keeps moving.

I’ve mentioned the happy accident of effect in Nosferatu. Decasia is filled with such images. At one point in his film there is a section of what looks like white-robed dancers of some kind, or even the meeting of a witches’ coven – it is extremely difficult to make out exactly, but that's beside the point. What it could be however, is one of the most atmospheric and mysterious representations of the meeting of the three weird sisters out of Macbeth that I have ever seen, with their ghostly, misty forms being more air than solid matter. These ghostly forms occur frequently throughout the film. Often the film is slowed down to the level of individual frames and so becomes a collection of phantoms, spectres, and ghoulish distorted presences. There is more to unnerve here than in many more traditional representations of ghost stories on screen.

Death imbues its presence throughout the screen. At one point we see standing nuns depicted in negative. This reversal is shocking and, with the line of children they are shepherding pictured advancing towards them, turns them into angels of death counting departed souls instead of anything particularly beneficent. Later, riders on a big wheel at a fairground are subject to a similar sinister operation as an enveloping blackness clouds across the image. The accompanying horn blasts on the soundtrack make it seem as if some deity or other is dispensing random, indifferent fates to the riders – this one, this one, not this one.

This darkness covers the sea too. We see footage shot from the mast of a ship, the film recalling Der Magische Gürtel, the First World War record of a U-Boat’s matter of fact destruction of merchant shipping. That film is shocking because the sinking of ships and goods is so plainly shown. Here, with bow of the ship shown in negative beneath swathes and swatches of damage, it appears as if it could be one of the very merchant ships destroyed, and heading towards its destiny.

This interplay between surface and image throughout maintains constant interest. After the whirling dervish at the commencement of the film (which sets up one of the film’s recurrent visual themes of spinning, turning and spooling) there is then a puff of cloud like an effect in an early Ali Baba film, after which the clouds gradually roll back to reveal the delights on offer. Later, in a shot of waves breaking on rocks, the surface of the film itself bubbles and cockles in liquid ferment. In the final section, as parachutists are pictured falling through the air – which is at the same time an exercise in falling through the uncooperative texture of decaying nitrate film, the film moves into a tracking shot as a black sun glints through the trees on the horizon. he parachutists have established a wartime theme, and suddenly the film itself erupts in shapes reminiscent of WW1 bomb blasts, followed by their spray of dirt.

There’s humour here too though, as with the boxer battling with the damage itself (and landing a knockout blow that causes the film to erupt into another scene); the painter in his studio where the damage of the print can stand for either the white heat of creative composition or the fact that he is so perturbed by his model that he is in a stew; and the miners knocking to see if they can hear life below, with the print damage resembling the noise waves that give them hope.

Tthere are some exquisitely lovely images too, such as the shot of people and camels travelling across the horizon, in a scene that calls to mind something similar in Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. The nitrate damage also has its own beauty regardless of interplay with the images it obscures. At times it is like watching a monochrome Stan Brakhage or Norman McLaren film.

In fact, one becomes a connoisseur of damage and patterning watching Decasia, watching the different effects, the filigree and the fronds, the coral and speckle and blotch and smudge, the solarisation and flare, the snakeskin patterning and staining, the wrinkles and buckles, the scratches and the scumbles, tears, blisters and puckers, the bubbling, the bloating and the crimping.

At the end of the film, the dervish is still turning, as if he is spinning his own decay, or even trying to prevent it as long as he keeps moving.

No comments:

Post a Comment