A virtual meeting place for diverse reviews, articles and podcasts on film written over the last decade or so. The title is taken from Boris Barnet's magical 1936 film, its name to me now synonymous with the ever-enticing possibility of beautiful and unexpected discoveries down the byways of cinema.

Thursday, 1 December 2016

Time Goes All Ways: The Chris Marker Collection

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2014)

__________________________

‘Prepare for a journey of (re-)discovery’ says Chris Darke in the booklet accompanying Soda Pictures’ Chris Marker set (2014), which seems sound advice as – a good sign for the inquisitive traveller I hope – I really don’t know what to expect from these ten films, all new to me, my knowledge of Marker half-formed at best, comprising a medley of partially remembered moments from his films – some recently viewed, some not seen for a decade or more – that may no longer bear much relation to the moments in the films themselves. So, as preparation, herewith my postage stamp, or perhaps postcard’s worth of virtual meetings with Marker.

First, of course, that moment of obliterating loveliness at the heart of the ciné-roman of his La Jetée when … but no, it can’t be said; even though everyone knows about it and everyone expects it, it remains a shared secret, a surprise with every fresh viewing. It’s enough that I know of no purer few seconds of film, with overwhelming desire crumbling into utter loss, all that is left upon waking the insistent thump of the heart, trying to break its cage. What else from La Jetée? The grabbing of a few moments of impossible happiness along the way as the film remorselessly heads towards its predestined ending; the brutal delicacy of the man’s out-flung arm at Orly.

Sans Soleil? Blonde children in sunlight. More recently, during a viewing of Marker’s 1966 film-essay, If I Had Four Camels, being awed by the train of innumerable visual correspondences and also slightly overwhelmed by the insistent intelligence of the narration which gave me no place to rest or relax. This feeling of missing so many of the subtleties in word and image also reminded me – possibly not inappropriately given Marker’s immersion in early computer technology – of being truly rubbish at early computer games such as Space Invaders; there, always another alien out to shoot you no matter how many you had already zapped; here, always another aphorism coming down the line – fail to grab it and process it immediately and you miss the next, and before long you are floundering, blasted by words ungrasped.

What else? A fascination with Hitchcock’s Vertigo; pseudonyms – Marker, Sandor Krasna; Marker himself peeping out from behind a piece of paper while sitting in a bar named in his honour in Tokyo in Wim Wenders’ Tokyo-Ga, and lastly the soundtrack to Alexander Medvedkine’s 1934 silent film, Happiness, which Marker re-edited in – I think – the 1960s, notably the moment of pure slapstick when, after clonking himself on the forehead with his crucifix to the ding of a bell, a priest dies like a frantic fly.

And that really is about the extent of my travels thus far on my Marker passport. I do have a couple of visas that may come in handy though. I know that dreams are integral to memory, and that memories can be indistinguishable from dreams. Didn’t Marker talk of Sans Soleil as a meditation on the dreams of the human race? I know that images from whatever source, whether witnessed in actuality or seen on screen, can mutate in the memory to correspond to the mind’s predilections, and that these images too can create what we might think of as false memories. However, these ‘false memories’, in their cohesive power, can fix and form our thoughts with emotional truth. I know too that borders between animate and inanimate are more permeable than is commonly imagined. Film and photographs can memorialise the actions and gestures of those who no longer walk among us, and the gestures of those preserved on film can transmute to those who see them who continue their life. In such manner gestures can cross continents and travel through decades, outliving the people who once carried them for a while.

And so, what do I find on planet Marker, as revealed by this ten film collection? Well, wise owls and grinning cats, playfulness, demonstrations, blood and batons, helmets worn to protect, identify and intimidate, words of witness, poetry, the Georgian painter Pirosmani as an avatar for Noah and a cat as the figurehead for his ark (or perhaps even the ark itself), Peter, Paul and Mary, Alfred E. Neuman of Mad magazine, the link between the biblical flood and the birth of mathematics, cowboys and Indians (but not the ones you might expect), Yves Montand, a bear on a leash, the collective wonder of an eclipse which, with faintly sinister echoes of La Jetée or John Wyndham’s The Triffids, turns the inhabitants of Paris into extras for an as yet unrealised science fiction, Snoopy, Chagall, an umbrella-wielding flashmob, pretty girls’ faces and a smile floating over a city. And much more. And if all of that sounds like an anarchic and uncontrollable menagerie, you can be assured that all make their appearances as part of wholly committed engagements with the subject at hand. Sometimes, filming action is direct and literally involved, as with the on-the-spot reportage, close enough to film the twitching of a military policeman’s finger in the demonstrations against the Vietnam war in 1968, while at other times the ongoing conflicts of the times are approached obliquely, as in his 1973 film, The Embassy. It’s perhaps best seen on the last film in the collection though, The Case of the Grinning Cat (2004), a wry commentary on realpolitik and the state of post 9/11 France given form and direction through an ongoing concern for a graffitied cat’s grin. It’s a trademark Marker tone that can only be made convincing through a combination of penetrating curiosity, active involvement and lightly-held wisdom. Briefly, seriousness of intent need not mean the ousting of whimsicality.

Which brings me to Letter from Siberia. So much of Marker’s output is about correspondence, in all its meanings, and this particular letter, joining those from China, Japan, Israel, Cape Verde and many other destinations throughout his work (of which the physical ones are but the most obviously situated), is a key early work. As a statement of intent, three decades before Jean-Luc Godard rat-a-tat-tatted his way through Histoire(s) du cinéma, it begins with a typewriter tapping out the credits as they appear. It tells us: words are as important as image here. Listen well.

And sure enough, we soon find ourselves liberatingly unmoored from a conventional appreciation of place. It might share the saturated palette of a 1950s National Geographic photo-essay but that really is as far as such a comparison goes, that magazine’s tone of one-world folksiness rejected in favour of a commentary that is more personal, partial, poetic, wry, tricksier and open-ended. And one that knows full well that descriptions distort so approaches the subject from unexpected directions – including animated inserts on such subjects as the history of the discoveries of mammoths – to get to the heart of things.

We are shown a land pitched between shamanism and the economic planning office, between the age of the mammoth and the age of the scientist, a place where a hobbled black horse can disappear into the forest and reappear ‘instantly in a Yakutsk legend a thousand years earlier.’ Time goes all ways here, as it should.

There’s childlike excitement: ‘I’m writing you this letter from the land of childhood; between the ages of five and ten this is where we were chased by wolves, blinded by Tartars, and carried away on the Trans-Siberian Express with our pistols and our jewellery,’ and there is poetry, both visual and descriptive. Take the shot of silver birches seen from the sky, filmed for an imaginary newsreel, ‘like owls’ tracks in the snow’, or the description of life and death, ‘separated by nothing more substantial than a breath of air’, accompanied on screen by the faintest wisps of cloud shading the land as they pass across a settlement. Then there are the the flowers preserved underground by scientists in discs of clear ice through a long and colourless winter - pink chrysanthemums invested with as much magic as the ribbons and ex-votos we later see festooning a magic larch tree. There’s wry humour too: ‘culture is what’s left behind when everyone’s gone home’ says the narrator to accompany shots of an empty Soviet culture park.

After a description of reindeer as ‘wheat, flax, rowboat, Christmas tree, medicine chest, and sacristan, all rolled into one,’ Marker takes his appreciation even further with an animated infomercial, delivered by an owl - the highest of praise in Marker’s world - on the various uses of a reindeer, ended with a piece of random signage in Italian asking people not to take their bicycles into church. And yet, as I’ve mentioned, whimsical invention dances with seriousness. There follows an experiment in the spirit of Kuleshov, in which a short clip of daily life and construction in Yakutsk is given three different voiceovers – one enthusiastic, one damning (as the times demanded) – and one more or less objective, which Marker admits fails to adequately capture the spirit of the place. Hence his multi-faceted approach.

There is also a sequence on gold panners, whose description requires reading in full. ‘But the lone prospectors have never gotten over the fever. And perhaps they never will. Tolerated at times, outlawed at others, they live in the wake of the dredges like gleaners on the heels of harvesters. Sometimes they’re drafted for menial work, but most often they’re left to their own devices. They may well be the only Soviet citizens not to benefit from social security, pensions, and free medical care. There is no earthly reason for them to go on. Do they have some higher motivation? I’m not so sure. There is scarcely more freedom in their individualism than there is gold in the mud they sift. However they’ve been handling them both for so long now that at times they forget which one they’re looking for. And perhaps in the last analysis they’re not prospecting for gold at all, but for mud.’ Change the accent to Bavarian inflected English and you have a character and narration that are pure Werner Herzog.

All of which goes to say: there’s a lot here.

Taking any overarching lessons from Marker is against the spirit of his enterprise, and a different selection of films would occasion differing thoughts, but one lesson seems to hold good. His films encourage us to look, and look again – and then connect, as he still does. Borders are permeable, and time goes all ways.

In Good Hands: Cape Forlorn (EA Dupont, 1930) and Double Confession (Ken Annakin, 1950)

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2014)

__________________________

It’s always welcome, cinematically speaking, to know that you are in good hands. Here I’m referring to those unassuming films which you come to without any great expectations, but which soon make you sit up in your seat and take notice, confident that you will be well served by what follows. The film that gave rise to these thoughts is Ken Annakin’s classy little seaside crime mystery from 1950, Double Confession, which, in a couple of rotations of a fairground wheel that serves as backing for the credits, convinces you that something good is on the way. The first shot, looking up at the wheel and held for 40 seconds, allowing it to follow its own stately pace, is assured and confident; while the second shows the wheel from the other side, now silhouetted against the sky as the music also heads into darker territory. Seeing Geoffrey Unsworth’s name listed as Director of Photography just a short while later comes as no surprise, even at only one minute in. There are various subcutaneous messages in the shots to mull over later, for example the two shots, one light, one dark and their relation to the title and the main characters, and the turning of a wheel of fate, but for now, the main thing is the air of confidence that the film imparts, and which is only reinforced by the shots – men’s shadows caught in the train smoke on the railway platform, the richly inky darkness of the night-time cliffs, whose outline down to the cove is an inverse to the big wheel which opened the film, the sharp creases in William Hartnell’s trousers – which follow soon after.

A strong and pertinent opening also characterises the main film I want to look at today, which is EA Dupont’s Cape Forlorn, from 1931.

Now, when a film carries a title such as Cape Forlorn, it’s fair to assume a less than upbeat trajectory to proceedings, and so it proves. For a description, let me quote card number 9 in the 3rd series of Wills’s Cigarettes ‘Cinema Stars’, issued in 1931, on which is written: “Cape Forlorn is a grim story of a man whom a storm flings into the life of three people virtually imprisoned in a lighthouse; the Captain, his wife, brought from a gay life at a seaport to the utter loneliness of the lighthouse, and the captain’s mate, infatuated with the woman. The man senses the undercurrent of tense emotion, and is himself drawn into it when he falls in love with the woman and she with him. The story moves slowly and tragically to the finale.”

If the story is that of fated melodrama, whose very ingredients predestine a bad ending, the visual design through which this is told is exemplary. With its emphasis on visual counterpoints to the characters’ situations, the film has one foot in the silent era, and indeed, its art director was Alfred Junge, who had cut his teeth at Berlin’s UFA studios in the 1920s before coming to Britain along with the film’s director, EA Dupont. Later of course, Junge found high acclaim with the work he did on films such as Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death and Black Narcissus.

As with Double Confession, from the very start, Cape Forlorn makes you sit up and take notice. It opens with a bravura two-minute tracking shot which begins, provocatively, by following the slow wag of a woman’s skirt as, to the sound of a Hawaiian guitar and the breaking of waves, the camera weaves between outside tables and palms before making its way into and along a busy night-time bar, where people gather for many more reasons than the probable outcomes of the evening. Embracing couples, sailors, dancers and chancers mingle in a fug of smoke and alcohol. And in a circular glide that pre-empts the shape of the lighthouse in which the main action is going to take place, the camera leads us around to a hula dancer gyrating beneath a large statue of grass-skirted legs, before we cut to two women at a table. It’s a tremendous start – more ambitious but equally as effective as another celebrated travelling bar shot that occurs in Dupont’s 1929 silent film, Piccadilly.

As for the two women in Cape Forlorn, Eileen is soon to head off to live with an older man in a lighthouse on a rocky New Zealand outcrop. Her companion is not convinced by the wisdom of this, and says, in a voice soused in end of the night huskiness, ‘do you think you can give this up? You’re crazy’. Eileen’s reasons for leaving are in fact left intriguingly obscure, but one suspects, given the film’s opening, that it is connected with, let’s say, warding off a fall into the unwanted base practicalities which come with the necessity of earning a living in such a locale. ‘At least he’s giving me a home,’ she says.

And soon enough, her photograph of the lighthouse becomes the real thing, and we are there, although we aren’t allowed even a brief honeymoon before the damp and the confinement and the continual surge and crash of waves do their work. ‘On a clear day you can see the mainland,’ says her new husband, the lighthouse captain Bill Kell – played by Frank Harvey, author of the play from which the film was adapted – as he shows his wife around her new home. ‘Just to show you how far away you are,’ mutters Cass down below to Parsons the general dogsbody, played by Donald Calthrop, who, despite playing the fool, adds an indefinable air of deviousness and shiftiness to the film. Most might recognise him now as the blackmailing heel in Hitchcock’s Blackmail.

‘Anything wrong my dear?’ are the first words we hear after this exchange. ‘Oh, nothing, only we haven’t seen the sun for weeks,’ replies Eileen. ‘That’s nothing, wait till we get a spell of fog,’ chips in Cass, who later prowls around the lighthouse – stalking is only just too strong a word – catching Eileen in different rooms, conversing with her at ankle height with her on a ladder, stroking her drying stockings in the kitchen, as he tries to tempt her with talk of a new life in Sydney. His physical presence is certainly more appealing than that of her husband, whose affection seems to be limited to pats on the back of the head or a playful tug of the ear. Nor is his bedtime manner or conversation up to the mark. ‘Another day gone. Three more years and we shall have a place of our own,’ he says as the rain lashes against the window and and the waves crash.

In her negligee, Eileen dangles her legs provocatively – and fruitlessly, unless she really was wanting a friendly pat on the head – over the edge of the bed. ‘Here, get my other watch out of the locker,’ says Bill, adding, with no sense of irony at all, ‘this one’s losing time’. As she does so, Eileen spies a few treasures of her own and prepares a surprise for Bill, a surprise we see in extreme close-up as she tips her lashes with mascara and brushes the light through her hair. Alas, her efforts do not go down well. All made up, she stands coquettishly before him, but he acts as if he has never seen a woman before, let alone one in make-up. Her poise slips and her face turns to nervousness as behind her the shadow of the window turns to a threatening spike of darkness with the arc of the lamp, its light washed away in a sweep of rain. Her scent and make-up are thrown to the sea before Bill grabs a towel and cruelly and crudely smudges the make-up across her face. The slap is unseen and unheard but nevertheless implied. Later, Eileen tiptoes down to see Cass. There follows a stormy night and a shipwrecked man. The next morning clears with the shriek and cackle of gulls around the lighthouse, acclaiming the next act of the play.

There’s plenty to satisfy here. As noted above, the dialogue trembles with implications throughout. ‘I’m going fishing, Mr Kingsley, would you like to come with me?’ says Eileen to the shipwrecked man who has taken her fancy, the scene ending with trapped fish shown gasping in a net, another little comment on proceedings from the natural world. Later, there is a marvellously startling moment as Cass, looking uncannily like a demented Roy Hudd, peers out from his window as he lathers his face and chortles and cackles with the gulls at the would-be lovers beneath, his laughter running into the very next scene, hours later.

It’s the design and art direction that really catches the eye though, whether the reflected light rippling on the arch of a window as Eileen polishes knives in the kitchen or the continual surge and break of the sea against the rocks, and the wind whistling through and around the tower. It’s in characters creeping around around the winding light-slicked lighthouse steps as lightning flashes briefly marble the inside walls and it’s in Cass and Kingsley confronting each other, the light sharding the window bars once more, and then illuminating the gun under the clam shell, its chambers filled with bullets. It’s in a brilliantly-judged shot from outside a lighthouse window, through which we see Cass panting in his death throes as he fixes his eyes on Eileen, his face set somewhere between Burt Lancaster’s and Grock the Clown’s, before the camera pulls Eileen and the rain on the window into sharp focus, leaving Cass a background blur. And it’s in Kell interviewing Kingsley as a Maori carving looks on from the wall behind and a fishing net is spread like the wings of a black bird, which when the shot opens out resembles a ragged black avenging harpy.

It all ends with a locked door, Eileen back in the bar telling her hopes to an empty chair and a whirling, giddy camera surrendering to the lure of the night.

Patches of Prepared Darkness: Val Lewton and The Curse of the Cat People

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2014)

__________________________

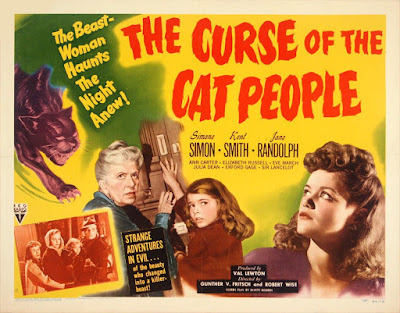

Today I’m going to look at a finely-judged, sensitive portrayal of childhood imagination, before which adult reason and psychology stand helpless – none of which you would glean from the film’s title, which is The Curse of the Cat People, produced by Val Lewton and directed by Robert Wise and Gunther von Fritsch in 1944. That misalignment of title expectations and subject really encapsulates the area I want to explore today, Val Lewton’s time at RKO, which requires a little background.

In the wake of Orson Welles’ loss-making Citizen Kane, RKO’s new head of production, Charles Koerner, announced a strategy of ‘showmanship instead of genius’ for the studio. In the event, in the person of Val Lewton, hired to head his low-budget horror B-movie unit, he got both. When presented with minimal budgets, little time and a run of lurid titles, Lewton, along with his collaborators such as directors Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise and Mark Robson, cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca and writer DeWitt Bodeen, produced films that entirely transcended genre expectations and proved once again that artistic invention and creative ingenuity often benefit from straitened circumstances.

Lewton sometimes talked of his pictures as if they were the simplest thing in the world: ‘a love story, three scenes of suggested horror and one of actual violence. Fadeout. It’s all over in 70 minutes,’ but what this underplays is how rich they are in allusion and atmosphere, as they trade on vague dread and primal fears. ’We tossed away the horror formula right from the beginning,’ he said. ‘No grisly stuff for us. No mask-like faces hardly human, with gnashing teeth and hair standing on end. No creaking physical manifestations. No horror piled on horror. You can’t keep up horror that’s long sustained. It becomes something to laugh at. But take a sweet love story, or a story of sexual antagonisms, about people like the rest of us, not freaks, and cut in your horror here and there by suggestion, and you’ve got something.’

On the back of Universal’s hit the previous year with their Lon Chaney vehicle, The Wolf Man, and feeling that although vampires, werewolves and man-made monsters were getting a little too familiar, little had yet been done with cats, Charles Koerner gave Lewton the title Cat People and told him to make something of it. Originally, Lewton thought of adapting Algernon Blackwood’s story, Ancient Sorceries, about a man who breaks his train journey in northern France and inadvertently finds himself in a town whose inhabitants, he comes to realise, have him under close watch while all the while feigning indifference in a distinctly feline manner. (‘The town watches him as a cat watches a mouse, says the narrator.’) Then the landlady’s alluring daughter arrives and the man finds himself falling under her captivating spell, drawn by an ancient call.

Although little remained in details from the original tale, one can see why it would have appealed to Lewton. The first half of the story, in which the man acquaints himself with the surroundings of the medieval town in which he finds himself, is filled with shadowy glimpses, sudden uncanny disappearances and a feeling of uncertainty and unease. There’s a telling phrase there too that would have lodged nicely in Lewton's mind: ‘The people did nothing directly. They behaved obliquely’. Which is also, as it happens, a pretty good description of Lewton’s own approach to his remit of producing B-movie horror pictures.

Instead of Universal’s monster-driven approach (which his publicity department, as we shall see, would undoubtedly have preferred and which they went ahead and promoted anyway, regardless of the evidence of the films), Lewton was trying to rethink the area of horror, imbuing it with a little intelligence and class. So, at this juncture, he made some extremely good decisions about his film. He figured, rightly, that instead of a story set in foreign parts, a tale about regular people set in contemporary New York would introduce a disquieting sense of familiarity to proceedings, so he thought afresh about the story and set about scripting an original treatment. After a viewing of Paramount’s 1932 film, Island of Lost Souls, specifically the ‘panther woman’, he realised that any attempt to make up their lead actress to resemble a cat in some way would take them down a very different path to the one he wanted to take, so he rejected that too. Finally, and importantly, he realised that if, as in Blackwood’s tale, he made his lead the man, the audience would always see the woman as a threatening outsider; if on the other hand, he made the woman his lead, and a sympathetic one at that, then the viewers’ feelings would be more engaged. Indeed, in the film it is the ‘plain Americanos’ Oliver and Alice who are the outsiders to the pitiable Irena’s world.

In the film, a woman fears that she is the cursed product of an ancient bloodline and that sexual intimacy or jealousy will unleash the predatory feline that lies within her – a notion that leaves her understanding American beau nonplussed and seeking advice from his workmate Alice, about whom Irena has good cause to be anxious.

The swimming-pool scene in which Alice is menaced by shadows on the walls, the night-time stalking to the rustle of bushes, the ‘Lewton bus’ which unfailingly jolts one alert even when you know it is coming – these are already so deeply embedded in movie lore they require no more discussion here. Another particularly impressive aspect to the film is its hinterland. It’s not directly about fear of the foreigner or incomprehensible ancient ways far removed from new world understanding but this certainly adds piquancy; likewise the treatment of sexual problems which is frank for its time. It is, in the end, all about shadows, real and imagined, in the streets and in the mind. As Lewton once said, ‘audiences will people any patch of prepared darkness with more horror, suspense and frightfulness than the most imaginative writer could dream up.’

Crucially, Cat People made RKO a heap of money and bought Lewton some tolerance for the artistic licence he had already shown, and which he would further indulge in the films which followed. Then a sequel to Cat People was called for and Lewton was given the title The Curse of the Cat People.

A brief aside on titles is worthwhile exploring here. While Cat People was in production, Lewton was given the title for his next project, a title which no doubt made his jaw drop and his shoulders sag, but the title of his next film it was going to be so he might as well make the best of it: I Walked with a Zombie. What he did with this was inspired. He researched voodoo and settled upon a very loose remake of Jane Eyre set in the Caribbean. And the very first lines we hear, as we see an enigmatic couple walking along a beach as the evening sun catches the roll of the waves, are spoken by a pleasant female voice who says with a little laugh, ‘I walked with a zombie – does seem an odd thing to say. Had anyone said that to me a year ago, I’m not at all sure I would have known what a zombie was.’ Boil lanced, ridiculousness addressed, title over and done with, the film goes ahead on its own terms with barely a minute on the clock. Lewton’s next film, The Leopard Man, is not as you might expect about a male equivalent of a cat person but rather a show promoter who owns a melanistic leopard that escapes.

And so to The Curse of the Cat People (which Lewton wanted to call ‘Amy and her Friend’; he didn’t get his way). Reprising their roles from the original movie, Kent Smith and Jane Randolph play Oliver and Alice, now married and with a flaxen-haired 6 year-old child, Amy, whose inclination to dream up imaginary playmates leads Oliver to suspect the lingering influence of his first wife, Irena. Then – on a ring thrown to her by a woman from the window of a mysterious dark house – Amy makes a wish for a friend, bringing Irena into her life, and something has to give between child and parents.

In the most passing of ways The Curse of the Cat People does provide some of the requirements for a sequel of the name. There is a ‘curse’ of sorts – in the meaning of a trait that has been passed on to a new generation – though it is entirely benign (it even saves Amy at one point) and leached of any of the connotations of sexual violence that appeared in Cat People; there is a woman who returns from beyond the grave, though as fairy princess and playmate rather than blank-eyed zombie requiring vengeance, and there is also a threatening dark house on the corner with its cranky, mysterious inhabitants. If we discount an early shot of boys playing at machine-gunning a black cat on a branch – something that sits badly with the rest of the film and which was added at the studio's insistence – there is barely a cat in the film. (Alas, the studio also removed a far more meaningful shot of Amy looking at a picture of Sleeping Beauty in a book – a picture that resembles Irena’s costume and helps to further blur the question of whether Irena is entirely imaginary or not.)

Tantalisingly poised between fantasy and gothic horror, pointed with references to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Unseen Playmate and Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and dabbed with subtle touches of shadowy darkness, The Curse of the Cat People disappointed RKO executives who were after the quick buck-making supernatural thriller that their fevered publicity department went ahead and promoted anyway (‘The Beast-Woman Stalks the Night Anew!’; ‘The Black Menace Creeps Again!’). In giving over its central space to a child’s imagination, what Lewton made was more lasting though.

Central to the film is the performance of the 7 year-old Ann Carter, who is as trusting, wilful, furtive, as lightly contemptuous and as deeply serious as only a 7 year-old can be. Her performance is complemented by genuinely strange elements such as the lithe and haunted Elizabeth Russell slinking around the dark house as the disowned adult daughter, the odd jarring filmic shock and the delicate touches that Lewton always crafted throughout his films.

One scene shows such touches very well. It is Christmas. Amy has gone into the snowy garden to give Irena her gift, and Irena has responded by calling up a magical twinkling of fairy lights. Then Alice calls Amy from the house and, briefly, a shadow passes across Irena’s face that resembles something like jealousy, before it goes as quickly as it came. If you’ve seen Cat People however, it calls up the memory of Irena’s transformation before she attacks Dr Judd, again done with little more than a selective darkening of the image. Irena kisses her and stands to wish her a merry Christmas, and there, by her head is a single icicle glinting from a branch, deliberately placed there I am sure to recall the Dr Judd’s swordstick that pinned Irena’s shoulder in the earlier film. Amy runs inside and for a brief moment, constructed out of nothing more than the shadow on the glass pane of the door and the Christmas tree within, it seems as if there is a weirdly undefined ameobic shape of spreading darkness. Three easily missable but highly crafted effects in 30 seconds of film. Even if you don’t consciously register them, they aid the general atmosphere.

Lewton’s films are sprinkled with such effects. In The Leopard Man, they can so brief as to be practically subliminal: a shadow of a dancer flitting across a fountain, gone as soon as it’s seen; the reflected ripple of water from under a bridge; a woman’s shadow briefly separating from herself in a night-time street as she passes a trash can; the subdued squeal of an organ note that takes half a minute to fade out, just present enough to set nerves on edge as the wind starts to rustle the trees.

As I have mentioned, these films are all about shadows. The previous year, Hitchcock had made a film noir in the bright light of day, Shadow of a Doubt. In The Curse of the Cat People, Lewton showed similarly threatening shadows, this time of the unseen and unquantifiable, latticing a plain old American shutterboard house, and in doing so cautioned that reason cannot vanquish all.

At a screening of his A Story of Children and Film recently, Mark Cousins implored the audience to watch his film with wide-eyed childish wonder (always good advice). I mention this because The Curse of the Cat People is the end point of a story, one of whose beginnings was the lurid, lycanthropic shock-horror of Universal’s The Wolf Man. This mutated into the psychological subtlety of Cat People which then spawned a film about the power of a child’s imagination. Much like cinema itself, it belongs to the child within us all.

Corrosive Desire: Brief Ecstasy (Edmond T. Gréville, 1937)

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2014)

__________________________

Anyone who has dipped into the volumes of Ealing Studios rarities (14 volumes from Network) will know that there are some real treasures to be found there, and none more than the film I’m going to look at today, Edmond T. Gréville’s Brief Ecstasy, from 1937.

The film’s story certainly conforms to a classic outline of romantic melodrama; a man and woman fall hard for each other the day before he flies off to Ceylon. He returns five years later, his marriage proposal sent but never received, and finds she has married a man twenty years her senior, whereupon the claims of duty and marital vows are set against the tugs of the true heart. However, the treatment of this story is fresh and bracing, brazen even. Graham Greene cut to the quick of the matter in his tart but acute review of the film in 1937, saying, “The subject is sexual passion, a rarer subject than you would think on the screen, and the treatment is adult: there isn’t, thank God, any love in it … the story is of the struggle between tenderness and sexual desire.” He continues, “with so bare a plot Mr Gréville has time to dwell on everything other directors cut: the ‘still-lifes’: the husband’s trousers laid pedantically in the press, while the wife beautifies herself in the bathroom for nothing at all. Other directors have to ‘get on with the story’. Mr Gréville knows that the story doesn’t matter; it’s the atmosphere which counts, and the atmosphere – of starved sexuality – is wantonly and vividly conveyed.”

He’s right, there is a style and suggestiveness here rarely seen in British films of the period; its characters are undressed – not literally of course, this being 1937, although there is one rather cheeky scene of Helen (or Hillin as she is known in the clipped accent of the times) looking into a mirror that cuts off at her collar bone – but rather in the way their motivations and needs are so apparent. Linden Travers, her eyes of doe-eyed defencelessness shot through at times with a kind of hopeless determination, plays Helen; Hugh Williams – an anthracite slick of hair above dark, untrustworthy eyes – Jim, the airman she meets the day before he flies out to visit his sick father. Paul Lukas – fortune, fatalism, fear and possessiveness flitting like clouds across his eyes – is Paul Bernardy, a metallurgy professor whose speciality, in a nicely ironic touch, is resistance to corrosion, and Marie Ney is his brisk, jealous housekeeper Martha, scornful of his younger bride having herself carried a torch for her master for twenty years. At points, peering hawk-like through the glass panes of a door at the couple, it looks like she could be auditioning for the part of the mother in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath. If this is an admittedly unlikely film to come to mind, there’s plenty about the style of Brief Ecstasy, distinguished by Ronald Neame’s tight and effective cinematography, that calls up continental comparisons, not least in its shadowy, even expressionist, touches filmed in the house itself.

The film’s brisk opening few minutes swirl us headlong into Jim and Helen’s affair. After the crackled glaze of the title’s lettering, credits roll over curtains billowing from the breeze through an open window at night, a shot, we will learn, from a climactic scene that gusts all the key elements – passion, frustration, defencelessness behind locked doors – through the film; the same fateful wind that later blows Jim’s unread telegram into a pile of rubbish. Then we see a sign for ‘The Snack Bar Hub’ in a halo of rotating lights, moving in the same direction as the spoon we next see stirring a cup of coffee on a counter in a cafe. Jim walks in, framed in a triangle of sunlight and staircase and uses the phone, the poster on the wall behind him of a woman calling out into his ear. His eye is taken by the woman sitting next to him, as hers is taken with him. Glances back, forward, back and forward, before he elbows the cup into her lap as he leaves, executes a circle of apology that continues the whirling of the opening and borrows a cloth from the waiter to pat her down, which he does, suggestively, raising her skirt above her knee as he does so, for which he gets a deserved slap. She storms out, forgetting her handbag which just happens to have her address on a tag.

It’s a short journey from here to the spume of overflowing champagne – six times before it finally falls flat into the glass – at a club after Helen reluctantly yields to his request to come out with him. Her neighbour Marjorie knows the score. When Helen says that she’ll be back in half an hour, she replies that she won’t wait up for her. She was right not to, as she finds out the next morning when she greets the sight of Helen’s unused bed with a ‘good on you, gal’ look. There is a telling scene of Helen and Jim in the club. He touches her hand and, to a long fade-out of Miss Gloria’s ‘With You’, their surroundings turn into memory-dreams. Earlier, Jim had slowly and deliberately appraised her after he asked her to dance: ‘Just like this? Look at me,’ she says. ‘I am looking at you’ he says, and does, as silhouettes of the band play on the wall behind them. Now, Helen responds in kind, lingeringly appraising him as he looks away. It’s only a couple of seconds but it’s enough to change the tenor of the film. Love would involve a smitten couple looking at each other in mutual adoration. This is far more calculated, an individual weighing-up of physical prospects. The next morning brings an exhausted couple climbing the stairs to her flat, filmed in such a way that we are unsure if it is one person or two, so much in rhythm are their steps.

And later on in the film, when the couple have been stranded at a pub for an evening after an unscheduled stopover, Jim leans in to kiss Helen in her bed. It’s a perfectly good shot with no reason to break the melodramatic continuity of action, but Gréville cuts all the same, and by doing so creates a scene that is far more interesting, and mutually satisfying to the characters’ intentions. What he does is change the angle of shot so we now see the same scene from above. Helen continues Jim’s forward movement, lying back submissively to his presence. It’s a movement of mutual longing, all the the more suggestive for being so deliberately achieved.

The characters’ sexual motivations are evident, but the film also has a firm undertow which goes unremarked in Greene’s review – the theme of ownership and property. Helen starts out as Professor Bernardy’s favourite student, before becoming his assistant and then wife. He then persuades her to give up this role and remain at home; ‘why not rest and enjoy your life?,’ he says, ‘just settle down here and be Mrs Bernardy.’ And so she does, giving herself up to the care of a house – much to the housekeeper’s pronounced distaste – in which the ageing professor can guard his possession. Their marriage drifts into pronounced solicitousness, forehead-pecking and boredom; desire quashed by the sight of socks and slippers by the fire and frustrated by a sleeping husband. The numerous shots of hands turning keys in various locks throughout the film are telling in this regard, as is that of Paul, the stern man stalking his property, alive to the possibility of deceit within. All Helen and Jim can do is role-play their past in the dusty light of an attic, while Martha snoops on the stairs outside. At the end, as the spurned lover starts up his motor in the darkness outside the bedroom window and drives off into the night, Paul closes the windows and draws the curtains that we saw at the beginning of the film, before standing above Helen and grasping her proprietorially by the shoulders; assertive ownership trumping corrosive desire.

Memories on the Wind: Silence (Pat Collins, 2012)

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2013)

__________________________

When a film calls itself ‘Silence’, you can, I think, be excused if it passes you by without claiming your attention. Do seek it out though; it’s a lovingly-crafted exploration of the experience of rootlessness and belonging, in which a sound recordist leaves Berlin for his native Ireland to record the sound of locations as far removed from man-made interference as possible.

Any journey into a space of reflective quiet is also, inevitably, a journey into one’s self and one’s past. ‘Are you going to go home?’ asks a woman of Eoghan, the sound recordist (the film’s co-writer Eoghan MacGiolla Bhríde), early in the film. ’No, won't be going that far,’ he responds, as if home were purely a question of physical place, ‘don't particularly want to go.’ But go he does, for work, ‘purely work’, as he says, believing that he can remain at a distance from the places in which he listens and records. And yet, as a voice we hear from later in the film says, ‘such an old, humanised country that we have; two-way transmission between people and places.’ The woman he is leaving also knows better than he his trajectory: ‘and so I follow the arc of life and return to my starting place,’ she says. And so he does, first gliding hermetically westward along the autoroutes of Europe as images from home – a couple by the range in a kitchen, sun and bonfire-lit super-8 memories – flicker through his mind, and then, by the wayward but certain route of an inner compass across Ireland to end up at his birthplace on Tory island, off the north-west coast of Donegal.

The film opens with the words, subtly altered, of the final stanza of John Burnside's poem, Insomnia in Southern Illinois, from his collection, Black Cat Bone:

The cuckoo calls from the well of my mind,

more echo than thought as it fades through the wind

and flickers away to the silence beyond

like the voice, in myself, of another.

The original has ‘the barred owl calls…’, but the cuckoo provides a richer, and more geographically appropriate, symbol of migration and uncertain belonging. For all the excitement occasioned by its seasonal return, it’s a creature that outgrows its host environment and flies away – a link made explicit a little later in the film when Eoghan makes the call of a cuckoo in The Burren at dusk by a campfire and is answered. The line ’like the voice in myself, of another’ is the pertinent one here, though. It tallies with a phrase in an earlier poem from the collection, The Listener – ‘something like the absence of ourselves from our own lives’ – which is perhaps the same thought seen in a different light. It’s this space in which the film takes place, not just the physical land and soundscape of rural Ireland, but the mental landscape of a man unmoored from his past and his heritage; in the distance one travels from one’s own self, and the emptiness of returning to familiar places when the songs and the need, especially the need to be there, are lost.

Birds, in sound and story, are a theme throughout the film. The first person we see Eoghan talk to, listen to rather, is a publican, who shares a story about the starlings on an uninhabited Scottish island, which still mimic the noise of the mowing machines last heard there in the 1950s. Eoghan responds, ‘I’m not really collecting stories, it’s more quiet that I’m after,’ failing to realise how the two are intertwined. Later, when he talks to Michael Harding, who comes across him in the middle of a recording and invites him back to sup with him, their discussion revolves around the meaning of the Gaelic word for silence, alighting upon ‘the gap between noise … the in-between’. Harding talks of the silence he finds in his mother’s house, where she no longer lives. It’s ‘not the absence of aeroplanes, or the absence of wind,’ but something else that remains undefined, a ‘door into wisdom’ perhaps, that one gains by resisting movement. He prevails upon Eoghan to sing, which he does, though the tune peters out when he loses the words, and they discuss the pros and cons of being rooted in a place; the flip side of belonging – feeling trapped by circumstance, confined by heritage.

For all its apparent simplicity of approach – a man regaining his old tongue as he journeys west and ponders what he has left behind – this is a film assembled with subtlety and affection, in image as well as sound. Indeed, it’s a film in which sounds seem to seek correspondences and affiliation, as when the passing trams at an intersection in Berlin resemble the noise of a wind filling a tree in full leaf, or when the stick of rubber tyres on tarmac, or traffic heard from a bridge sounds like the wash and drag of waves on shingle. Later, on Tory island, a rock of unseen gannets heard against the waves could be children at breaktime in a playground.

Sounds from one location seep into another too, as when birdsounds of dusk enter onto a scene on Mullaghmore, or the noise of a passing car melds into that of a river at dusk. For all its emphasis on sound, as with the different character of wind in grass, in trees or in wires, there are subtle tonal variations in the look of the film too, as colours wind through scenes from Eoghan’s journey. The vivid yellow of a sign on a telegraph pole picks up on the gorse in flower by the river in a previous shot. And when Eoghan drives through the artificial yellow-grey light of a road tunnel, this same colour transmutes, in the next scene, to that of the sound editing software on his computer screen. As he listens to a trapped blackbird fluttering up against the glass he runs his finger against a damp window-pane, and we then move to a shoreline, whose rocks are slathered with the same yellow-green, this time of seaweed, as a curlew trills through the fog. The film is not above confounding us either, as when all sense of scale is lost in a slow pan of the camera on The Burren; is that a stone wall and a copse seen from high above, or a close-up of the grikes and clints of lichened rock? Later, on Tory Island, a dog barks in the distance, filmed from so far away its sound reaches us after the movements of its mouth.

At dusk one evening, Eoghan pulls apart the flowers of a hawthorn, perhaps to throw into a water’s flow, the petals sticking to his fingers and nails like so many memories that cannot be lost.

A man on the Atlantic coast talks of a ‘velvety texture to the stillness, made up of subliminal sounds coming in from great distances,’ as Eoghan turns a shell between his fingers. ‘It’s like listening to the sound of the past,’ he is told, ‘all the bits of the past that don’t get into history.’ At this, Eoghan looks over his shoulder and into a black and white past of families leaving for the mainland and weighting their dog for the water.

Another time, he tapes his microphones to the window as if he is conducting an EVP experiment to see what he can catch of voices of the past coming across the waves: song, a baby’s cry, a snatch of conversation. Perhaps he is listening for sounds of the fishermen of his childhood, singing to each other on a calm night across their CB radios.

And so, as Gaelic, a language more meaningfully rooted to the natural courses of the land in which it was shaped, begins to be spoken, Eoghan steps off the quay on Tory island to an indifferent welcome from the mewling gulls.

The film features many maps, actual ones of the terrain through which Eoghan is journeying to record his sounds, but many more, with neither names nor directions. There are those that resemble worn and ancient charts, like the yellowing birch bark that Eoghan sees as he runs his fingers through the mossy rowans and the tips of spring bracken, or the sedimentary layers of wallpaper and flaking paint on the walls of his abandoned family home. Then there are the maps of song, from Eoghan’s own mother singing ‘The Breeze and I’ to songs of love and parting, the words lost, and then the maps that birds leave in our lives, from the sparrows chirping in the middle of traffic noise in Berlin to the cuckoo, blackbird and curlew, and the corncrake that scrapes out its song in the background as Eoghan talks to an old resident of Tory Island.

All lead to what we have been flashing forward to in snippets throughout the film, tattered lace fluttering through a broken window in an old bedroom that looks out upon ruined walls and the sea. And the realisation that whatever silence Eoghan finds will be temporary respite from the claims on his life and time, and not one rooted in the depth of belonging. It is a place where many of us dwell these days. The land awaits our connections anew.

There Are Spirits Abroad In The Land: Ghostly Tales for Dark Nights

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2013)

__________________________

A notable theme threading through two of the three horror-themed vintage TV plays and series under consideration here – Robin Redbreast (Play for Today – James MacTaggart, 1970), Dead of Night (BBC series, 1972) and Schalcken the Painter (Leslie Megahey, 1979) – is that of the spirits of Old England awakening from their quiescence, to protest at the selling of their toil or to offer a reminder of their presence when they have been forgotten or disdained. Sometimes however, as in the BBC’s 1970 ‘folk horror’, Robin Redbreast, they never went away. It’s quite a find from the archives. Its arrival into a new age decades after its first broadcast seems appropriate for a story concerned with sacrifice and rebirth.

It begins with a cottage, a ‘before’ photograph of a cottage near Evesham to be precise, to which script editor Norah has repaired after a breakup and where her liberated, ‘modern’ ways of thinking meet far older channels of thought. The locals she meets are a curious bunch, if not unfriendly. There’s the sly and somewhat sinister Fisher (a tremendous Bernard Hepton), orchestrator of proceedings thereabouts, the inscrutable housekeeper Mrs Vigo, who exhibits a sort of patient and amused condescension for this city-dweller’s ways, and Rob the gamekeeper, who Norah is positioned into meeting, and then mating with.

She has moved to Flaneathan Farm, place of birds ‘in the old tongue’, as she is told by Fisher. Woman have always lived here, he adds. And what of all the cracked window panes in the house when she arrived? Birds that flew down the chimney and then tried to escape, says Fisher. ‘They should have known they had a way out, but being birds, they didn’t.

John Bowen’s dialogue – well worthy of a second visit – is full of non-sequiturs between Norah and villagers as she tries to elicit some – any – information regarding the real-life mystery play in which she finds herself, the rules of which are known to everyone else but her. ‘Why do you call him Rob when his name’s Edgar’ asks Norah of Mrs Vigo, ‘answer’s to it,’ she replies. ‘It’s not his name,’ ‘short for Robin,’ says Mrs Vigo. And where else would a Robin go but the place of birds? And how does a Robin get its red breast?

The longer Norah remains, the more her interactions are filled with foreboding. Early on, being cautioned by Mrs Vigo to keep warm a half-marble that she has brought in from her window-sill is one thing, but being heavily pregnant and told to her face, ‘come the winter, the dark days, you go where you will and no objection, no effort made to keep you, but now, come Easter, here am your place,’ is quite another. ‘She isn’t really a prisoner, this is 1970,’ says her friend Madge in London. But she is not there.

One can idly muse what difference the addition of music or a theme song would have made to the drama, from those musicians who were drawing deep from the wells of Britain’s folk and mystical heritage at the same time, but that would have changed the atmosphere, made the whole a little too muscular. Robin Redbreast’s unnerving atmosphere comes just from being set in the present-day where a veneer of normality is maintained. The dark traditions do not need to be called up; they are.

As long as you remain only momentarily diverted by the sight of Clive Swift’s fetching sage-green buckled trouser suit and cravat combo, Don Taylor’s The Exorcism is the most potent of the three surviving episodes of the BBC’s 1972 anthology Dead of Night, in which protest against the stifling mores and deracinated carelessness of present-day living are mixed into a supernatural setting. It’s a biting piece of social comment in which a Christmas dinner goes from bad to worse to intolerable to unimaginable, the play’s conceit being that an event can be so traumatic that its record is held in the walls where it occurred. If this sounds familiar it’s a theme also explored in Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape, which was in fact originally slated to be part of the series but eventually made as a separate production.

The play’s targets are set up from the off as four self-congratulatory types assemble in a couple’s newly renovated cottage. ‘We like the area and it’s reasonably convenient for London’ says host Edmund; ‘it’s friendly here – you know how a house sort of welcomes or repels you as soon as you open the door,’ says his wife Rachel, her words unwittingly revealing the truth that she has been welcomed to the house, but for a purpose she has not divined. ‘I think we should be concentrating on how to be socialists – and rich,’ says Dan on hearing how Edmund’s father disapproves of his purchase, each line more bait for a trap set to spring. The play’s dialogue justifies a second watch in fact so you can notice just how tightly scripted the piece is. When Rachel plays the clavichord, her husband remarks that the instrument is ‘just right for the cottage, small-scale, intense’. Indeed – though by the end its keys are detuned, its notes rancid.

Silver gravy boat in hand, Rachel calls the guests through to dinner at a table complete with a spotlight for carving. The lights go. ‘But I haven’t finished the pudding, or the coffee’ says Rachel. And nor will she, her body becoming the channel for the cottage’s previous occupant to issue a searing ‘cry against injustice from the dark centuries’ which has chosen its listeners and demands their hearing. ‘You know this is becoming a very moral tale … you throw a few switches and we’re back in the dark ages,’ says Dan’s wife, more presciently than she could have known.

Haunted house dramas are a film staple, but The Exorcism’s conviction, righteous anger (channelled, as in Robin Redbreast, through the privileged victim of choice, Anna Cropper) and sense of all-too plausible historical injustice lend it individuality and charge. When Edmund and Dan go to fetch candles after the lights go, Dan talks of whether it is society or technology that determines consciousness. His blithe reasoning misses another possibility however, one crucial to the matter at hand, that the past, its people’s toil, their deaths, their landscapes and their buildings, which we now buy and sell and in which we live, also shape consciousness, and you forget this at your peril.

From 20th century England we move to the Netherlands in the 17th century for the last of the haunted offerings I want to look at today.

In his 1968 programme for the BBC’s Omnibus series, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, Jonathan Miller made – as a way of introducing the themes and preoccupations found in MR James’s writing – an adaptation of James’s story of the same name. Notwithstanding its status as a personal documentary film essay, it stands as one of the best adaptations of James’s work. Schalcken the Painter, also made for Omnibus, this time by Leslie Megahy in 1979 when it was shown in the late hours of December 23rd, is a similarly genre-troubling piece, though its creative layers go even deeper. On one level it’s a ghost story - an effective one too, adapted from Sheridan Le Fanu’s tale of the same name; on another it’s a biographical portrait of the painters Godfried Schalcken and his mentor, Gerrit Dou; it’s also a parable about greed and covetousness, wealth and value, and, not least, it’s a meticulous recreation of the milieu and practices of Dutch 17th century painting, as exquisitely lit and composed as the canvases of Vermeer, de Hooch and Schalcken himself, from which it takes its cue.

‘In all the paintings I have seen,’ intones narrator Charles Gray about Schalcken’s work, ‘I have remarked a strange distance in the relationship of the human figures therein, contacts made only by the expected conventions and courtesies of polite society, or by commercial transaction. Sensuality without warmth, without passion, trappings that are ornate and lovely, and yet set in a darkness that the faltering lamplight or candle flame never seems capable of penetrating.’ There, in a nutshell, is the world of Schalcken the Painter. Indeed, as we traverse the tale, in which a mysterious man of ghastly aspect and pallor as grey as a tomb presents a coffer of unalloyed gold to buy Gerrit Dou’s niece and ward and Godfried Schalcken’s would-be betrothed, Rose Velderkaust, only for her to disappear entirely after she has been taken from Dou’s house, for much of the time it feels like the film is itself inhabiting a series of Dutch miniatures (it comes as no surprise that director Megahy credits Walerian Borowczyk’s 1971 film, Blanche for making him realise the possibilities of what he could do with the look of the film). Its sound is important too; it’s filled with the weight of silence of the rooms in which time passes, allowing sounds not normally heard – the scratch of a quill or charcoal on paper, the click of beads on an abacus, footsteps, the creak of a floorboard, the scrape of a brush through hair – to assume weight and portent.

The script might be spare, Megahy resisting advice to flesh it out a little, but the words that are used are lean and to the point. ‘Turn from the light … your breast bare … look into the dark’ are the opening words of film, spoken by Schalcken to his model, after which we see Schalcken, master of the effects of candlelight in his paintings, eye reddened by concentration in the flicker of a candle’s tall flame. (And that’s meticulous recreation for you – one candle flame is not like another, and the tall orange flames that flare so characteristically in Schalcken’s paintings are recreated exactly in the film.)

Later, when Dou and Schalcken await the arrival of the mysterious visitor from Rotterdam, Dou asks ‘Van der Geld?’ of the man’s name, ‘Vanderhausen’ responds Schalcken. Dou’s mind is firmly on the money. Indeed, gold seams and rills the film, from our very first sight of Dou counting his coins. Then there are the gold coins in Vanderhausen’s coffer, the pearls around Rose’s neck, the treasures of her marriage settlements, the tinkle of coins into a brothel keeper’s palm, the coins that Schalcken sprinkles into a model’s lap, the golden light of a fire as the painters enumerate their takings, the coins placed on Dou’s eyes at his death and those that Rose scatters at her feet from Schalcken’s purse.

‘Do you trick yourself out handsomely now’ says Dou to Rose before the visit of Vanderhausen, recalling the narrator’s words about the woman in the painting that sets the story off: ‘her features wear such an arch smile, as well becomes a pretty woman when she’s engaged in some charming trickery of her own device’. It’s a nice alteration from Le Fanu’s original, which has, ‘her features wear such an arch smile, as well becomes a pretty woman when practising some prankish roguery’.

Schalcken, played by an aloof and nicely testy Jeremy Clyde, in love with Rose but lacking the spine to make good on his entreaties of endearment after he unwittingly signs his name as a witness to her marriage contract (‘he was in love, as much as a Dutchman can be,’ says the narrator), reveals himself to be in thrall to the lure of money that so appeals to Dou. His impulse of love gives way to the impulse of ambition; Rose is left to her fate as the object of a marriage contract. As the narrator says, his is ‘a tale of heartlessness’.

Schalcken the Painter was much requested for a DVD release and rightly so. It’s a rare combination of intelligence and artistry – in all its forms.

‘If these young people are our future we are doomed’: Marlen Khutsiev’s I Am Twenty and Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers.

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2013)

__________________________

I want to look today at two films, both subject to censorship and official disapproval but which were also both, in Andrzej Wajda’s phrase, ‘authored by the spirit of the time’ – Marlen Khutsiev’s I Am Twenty (1961) and Andrzej Wajda’s own Innocent Sorcerers (1960).

I am Twenty – made in 1961, censored on completion, delayed, denounced by Khruschev and only released in a heavily cut form in 1965 – is a key Russian film from the era of the Khrushchev thaw, which allowed a certain freedom of expression in areas that were previously off-limits. In parts it is dreamlike, in others fresh and vibrant, while scenes of Antonionian ennui and even a supernatural interlude mingle into its overall portrait of unfocussed youth. It is a surprising film, wholly tied to its time but resonant still with its searching questions. It opens with three young soldiers walking between tram tracks in a damp grey Moscow dawn, pausing only to look into the camera as they pass – the meaning of which becomes clear at the end.

In essence the film is simple enough: Seryoga returns from his military service and hooks up once more with his childhood friends Kolia and Slavka, and together they negotiate the excitement, frustration and even boredom of growing up. They hang around, hang out, grow apart as romance and fatherhood come into their lives, grow distant, then realise they have been heading in the same direction all along. It sounds like a universally applicable storyline, but what’s remarkable is how it has been translated to the screen here. It’s pleasurable to see the film’s twists on commonplace tropes. I think of Seryoga, waking in the middle of the night. He walks outside, lights a cigarette and begins to walk. A muscular man in a tight white T-shirt walking his loneliness through rain-slicked streets under a thick white sky, while a crossing light flashes steadily at an empty intersection – sounds solid American, 1950s, but the sequence is lit in such a way as to make it more ethereal, and the piano notes of the score clash with the city’s low, resonant bells; then, to cap it all, as Seryoga walks, his voice intones fragments of Mayakovsky’s poem, ‘Past One O’Clock’, as they weave through his thoughts.

Another surprise – dancing appears regularly throughout the film; informal dances to a record player in the shadow of a tower block or in someone’s apartment, or to musicians on the street the day of exam results, the couples always tentative, a little stiff, as if not quite accustomed to the moves and unsure of what is allowed – a suitable symbol for the state of the country as a whole at the time perhaps. And throughout the film too, disillusionment dances with possibilities for expression and fulfilment. There’s a freewheeling exuberance to early scenes; meeting a friend, Seryoga flings himself down stairways, out into the street and into the rough and tumble of football on a patch of waste ground. The same feeling fills the clashing cacophony of the May Day parade, or a gutter–bashing day of snowmelt in spring, but these are interspersed with periods of deflation and uncertainty. There are unexpected dashes of humour too. As Seryoga drinks to disarmament and peaceful, constructive work with Kolia and Slavka in Slavka’s apartment, which he shares with his wife and baby, they tease the new father that he is ‘getting into the swing of consumerism’. ‘I am’, he replies, to which Kolia adds that he has ‘bought a bra and a floor lamp. You can’t stop him now.’

Unforced family life, humour, purposelessness, youth hanging around and filling in time – these are not things one really expects to see from a 1961 Russian film, and its extraordinary nature can be slow to dawn on the viewer used to seeing these everyday happenings in other film contexts. ‘Science nurtures youths, but not enough,’ says Seryoga to his mother before bed one evening as he smokes and reads late from a text book. His feeling of emptiness and need for guidance, need to lay down his trust in something worthwhile, is palpable, joining with the pervasive sense of characters in the film requiring something meaningful to live by as they try out various routes – fatherhood, romance, art, poetry, the ideals of the revolution.

The film enraged Khruschev, who singled it out for attack at a speech in 1963, denouncing the director and his collaborators, saying that ‘the characters are not the sort of people society can rely upon. They are not fighters, not remakers of the world. They are morally sick people. The idea of the film is to impress upon the children that their fathers cannot be their teachers in life, and that there is no point in turning to them for advice. The filmmakers think that young people ought to decide for themselves how to live, without asking their elders for counsel and help.’ It’s a distorted reading of a film which is notable for the honesty with which it broaches the subject of who the young should learn from, what they should learn, who they should respect and why, and what ideals they should live by. The ideas are perhaps commonplace, but all the more remarkable for being voiced in such a direct fashion at the time.

‘I already know everything you can tell me,’ says Anya to her father when he tries to dissuade her from leaving home to set up a flat with Seryoga – an attitude that would surely have fed into Khruschev’s denuncuiation, as would the man’s words to Seryoga: ‘you can rely on no–one, no–one will help you, not a single person. People don’t give a damn about each other, however regrettable that may be.’ His words do, however, harden Seryoga’s desire to find meaning and direction in his life. Things come to a head at a party held by friends of the woman he has been seeing. ‘What shall we take seriously?’ he asks, after proposing a toast to potatoes; potatoes brought in to the room to eat but which had been worn as a necklace and then trampled underfoot by dancers, potatoes that – as he had just heard before he left the house that evening – had kept his mother and his baby self alive for a month after she mislaid her bread coupons in the war. The party recalls Antonioni in its continual dissipation of focus, its momentary fascinations as easily let go as found, its desire to fill the moment with whatever entertainment is to hand. Seryoga walks out.

In one of the final scenes, Seryoga is at home in the night, troubled by his thoughts. He announces to himself and an ashtray of burning paper on a table that today is the turning point. ‘I don’t just want to wear out the days’ he says, and then, in a truly moving scene, his dead father appears to sit across the table from him. They greet, and talk through the veil of one’s death, the other’s life. ‘What’s for me?’ asks Seryoga, ‘living,’ responds his father. ‘But how? How?’ ‘How old are you?’ asks his father. ‘I’m 23,’ says his son, ‘and I’m 21,’ he replies. Seryoga’s gaze falls as the realisation of adulthood dawns and his father leaves with two comrades to resume his spiritual guarding of the Moscow streets, like the soldiers we see in the very first shot, looking at us out of the camera. The baton is passed, the responsibility is with the new generation. As Khutsiev said, the subject of I am Twenty is the maturing of man at that particular moment in history.

The problem with Andrzej Wajda’s 1960 film Innocent Sorcerers, as seen through the eyes of the powers that be at the time, was not the maturing of man but quite the opposite, the dissipation of youthful energy into frivolity and ephemeral fascinations.

Wajda says of his film that it was about a new generation of children who grew up in postwar Poland, a generation whose rebellion was against everything, against sameness and stagnation in language and dress and ambition, a generation who relished the clandestine sounds of jazz and devoured the occasional sightings of American films and their promises of unlikely freedom. Innocent Sorcerers is a film of that rebellion, or at the very least a film of young people looking for something that will make their life bearable.

Its central characters are the sports doctor and jazz drumming Lothario Andrzej and a gamine Clara Bow lookalike, who calls herself Pelagia. They meet thanks to the luckless machinations of a friend who originally wanted the girl, and head back to the man’s flat after she has intentionally missed her last train. There, in a wonderful 35 minute central scene that is erotic, tense, humorous and teasing and whose characters are amused, abashed, defiant, coquettish, competitive and companionable by turns, they pen an agreement about their meeting and the first steps of their apparent romance. They have gone past ‘boy meets girl’ and ‘first kiss’ (which they still haven’t shared) and have reached ‘illusions and bright conversation’. ‘Right,’ she says, adopting a mock serious voice, ‘before lying down we need to discuss the dilemmas of our time.’ ‘Really?’ says he. ‘What’s next?’ ‘It’s time to go to bed if you don’t mind,’ she responds, ‘sofa bed’ says he, ‘all modifications are possible,’ says she. And so they continue, playing out their measured game of not–quite romance, not knowing whether they are serious or not, their moves and conversation all the more charged for the promise of the assumed intimacy which they may or may not take up. It is as if they have already seduced each other, know each other’s moves and how to outwit them.

‘Older people say that we, young people, only see and listen to ourselves. It’s possible. But how could we be any different? Our generation has no illusions,’ says Pelagia (in the part of their game that requires serious talk). ‘It’s obvious to us that we know nothing of the world we live in,’ she says, and removes her necklace. ‘It’s the reason for our anxiety,’ she continues, ‘we know we’re lost and lonely’. She asks Andrzej what he cares about. ‘Comfortable shoes, good cigarettes, good socks,’ he replies.

Unsurprisingly, the film did not go down well. Reaction from the Party was, as Wajda tells it, along the lines of, ‘if these young people are our future then we are doomed’; while the church took a look at the film, considered a response and declared that, ‘if these young people are our future, then we are doomed’, deploring the ‘depraved values of an immoral generation’ who seemingly had no checks upon their impulsive capriciousness.

Wajda tells an amusing story about how far the feelers of censorship crawled across his film. In the opening scene, Andrzej turns on the tape player on the floor of his flat with his big toe. ‘It’s a disgrace,’ cried the censor, ‘it shows both contempt towards technology and to the labour of the worker who created it.’ That scene somehow stayed in, but everything else whose removal was requested had to go – including the original ending more’s the pity. After his film sat on the shelf for a year, Wajda was asked by the Minister of Cinematography – and if ever an official title gives us pause it should be that – to give his film a happy ending, in which Pelagia goes back to the flat to presumably wake a sleeping Andrzej. It doesn’t take too much imagination to strip that away and give it the real ending, the required one too, in which Pelagia skips down the stairs and out into the Warsaw morning, leaving the man she has left asleep, the two of them marked in some way by the encounter, perhaps to wonder in years to come what happened to the other; still sure of the strength of their armour but also feeling it a little closer to the skin than it was before their night together.

Friday, 18 November 2016

Mai Zetterling

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2013)

__________________________

Before I had ever heard of her as an actress or director, my somewhat unlikely introduction to Mai Zetterling was through a remaindered copy of her novel Shadow of the Sun, which – attracted by its Elisabeth Frink dustjacket of variously twined couples – I bought from a bookstall in Southampton Railway Station sometime in the early 1980s. Reading it, I entered its pungent world of madness, incest and mystical union, a world of outcasts and strays whose souls need a home, existing to one side of the society in which they find themselves. It’s a sense that is particularly strong in the semi-autobiographical main story of a troublesome child seeking a spiritual home and body.

My next encounter was some years later, when clearing out my mother’s house, I was distracted by reading through ageing piles of Hampshire, the County Magazine from the 1960s and 70s. There, in among John Arlott on books, cricket and villages and Norman Goodland on country matters, was, in the pages of the June 1970 issue, Mai Zetterling talking about the hidden treasures of Hampshire, getting her guests to gather sacks of leaf-mould for compost or taking them out for a fish supper in Portsmouth. It didn’t tally with the first impression I had gained from the novels, and nor did this square with the actress that I later came across in her 1940s and 50s English films. However, her 1985 autobiography, All Those Tomorrows, confirmed her as a shape-shifting being with amazing powers of reinvention, always the outsider, no matter how much she would have liked to fit in, if and when she cared about such things. Indeed, at the end of the book she writes, ‘perhaps I am a mad-hatter Swede who got lost in the world ... I feel very far from the norm of just about everything.’

She was the 14 year-old school dropout who became a voracious reader and the owner of a 12,000 book library, the teenage Stockholm girl in hopeless dead-end jobs with leery bosses, cutting out pictures of Tyrone Power from glossy film magazines who a few years later would be in a relationship with Tyrone Power; the fearful, hopeless, untrustworthy child who, years later, when asked what subject she wanted to pursue in the multi-director film about the Munich Olympics, Visions of Eight, chose wrestling because that was the thing she knew least about; the girl who worshipped Shirley Temple after sneaking into a Stockholm fleapit and catching sight of her on screen, whose 1966 film Night Games caused the same Shirley Temple to resign as director of the San Francisco International Film Festival in protest at its screening; and she was the serious stage actress who Jean-Paul Sartre described as ‘a tragedienne of our times’ who became a ‘dangle-dolly’ (her term) in a number of British films in the 1940s and 50s, when she was wince-inducingly dubbed ‘Britain’s swede-heart’ (she was, understandably, unimpressed by being made to sound like a prize root crop), and the aforementioned dangle-dolly who ended up directing social documentaries and feminist features in the 1960s and 70s.

Nor did critics know what to make of her when she left the zone of familiarity behind; ‘she writes like a witch’ said The Listener’s review of Shadows of the Sun, while ‘she directs like a man’ was one of the more nonsensical comments about her directorial feature debut, Loving Couples.

Although most of her documentaries seem destined to remain unseen or lost, at least a few of the films she made as an actress in England are available on DVD and it’s these I’ll take a look at now.

In Basil Dearden’s Frieda (1947), she stars opposite the saturnine David Farrar as the German girl who helps him escape enemy territory. He marries her, or half-marries her – she is Catholic, he not – under fire in a bombed-out church in No Man’s Land. He returns with her to his home in Denfield. ‘Nothing to be frightened of there’ he reassures her, ‘it’s like any other town in England’, somewhat underestimating the task of winning over the townsfolk by introducing a German girl into their midst while the war is still on. Casting a German girl in the part was still too contentious so soon after the war so Zetterling was chosen for her English language debut. Shy and fearful at first, clad in the protective layer of her leather coat, she is gradually allowed to relax a little into English life, and even let her hair down (quite literally as she loses her tightly coiled German braids) – but then a surprise Christmas visitor threatens to tear up all the careful groundwork of acceptance.

The following year she was back in Britain, after having returned to Sweden to star in Ingmar Bergman’s Music in Darkness, having a little fun in the Facts of Life segment of Quartet, the 1948 anthology of W. Somerset Maugham adaptations, as a smiling, thieving seductress whose wiles are unwittingly bested by the innocence of a young tennis player. Later, a twinkling streetwise scampishness does battle with a world-weary melancholy in her role as an author and imposter in the satisfying drawing-room comedy, Hell is Sold Out (1951), in which Herbert Lom and Richard Attenborough play the wartime prisoners of war who court her.