A virtual meeting place for diverse reviews, articles and podcasts on film written over the last decade or so. The title is taken from Boris Barnet's magical 1936 film, its name to me now synonymous with the ever-enticing possibility of beautiful and unexpected discoveries down the byways of cinema.

Thursday, 1 December 2016

Patches of Prepared Darkness: Val Lewton and The Curse of the Cat People

(written for a MovieMail podcast in 2014)

__________________________

Today I’m going to look at a finely-judged, sensitive portrayal of childhood imagination, before which adult reason and psychology stand helpless – none of which you would glean from the film’s title, which is The Curse of the Cat People, produced by Val Lewton and directed by Robert Wise and Gunther von Fritsch in 1944. That misalignment of title expectations and subject really encapsulates the area I want to explore today, Val Lewton’s time at RKO, which requires a little background.

In the wake of Orson Welles’ loss-making Citizen Kane, RKO’s new head of production, Charles Koerner, announced a strategy of ‘showmanship instead of genius’ for the studio. In the event, in the person of Val Lewton, hired to head his low-budget horror B-movie unit, he got both. When presented with minimal budgets, little time and a run of lurid titles, Lewton, along with his collaborators such as directors Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise and Mark Robson, cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca and writer DeWitt Bodeen, produced films that entirely transcended genre expectations and proved once again that artistic invention and creative ingenuity often benefit from straitened circumstances.

Lewton sometimes talked of his pictures as if they were the simplest thing in the world: ‘a love story, three scenes of suggested horror and one of actual violence. Fadeout. It’s all over in 70 minutes,’ but what this underplays is how rich they are in allusion and atmosphere, as they trade on vague dread and primal fears. ’We tossed away the horror formula right from the beginning,’ he said. ‘No grisly stuff for us. No mask-like faces hardly human, with gnashing teeth and hair standing on end. No creaking physical manifestations. No horror piled on horror. You can’t keep up horror that’s long sustained. It becomes something to laugh at. But take a sweet love story, or a story of sexual antagonisms, about people like the rest of us, not freaks, and cut in your horror here and there by suggestion, and you’ve got something.’

On the back of Universal’s hit the previous year with their Lon Chaney vehicle, The Wolf Man, and feeling that although vampires, werewolves and man-made monsters were getting a little too familiar, little had yet been done with cats, Charles Koerner gave Lewton the title Cat People and told him to make something of it. Originally, Lewton thought of adapting Algernon Blackwood’s story, Ancient Sorceries, about a man who breaks his train journey in northern France and inadvertently finds himself in a town whose inhabitants, he comes to realise, have him under close watch while all the while feigning indifference in a distinctly feline manner. (‘The town watches him as a cat watches a mouse, says the narrator.’) Then the landlady’s alluring daughter arrives and the man finds himself falling under her captivating spell, drawn by an ancient call.

Although little remained in details from the original tale, one can see why it would have appealed to Lewton. The first half of the story, in which the man acquaints himself with the surroundings of the medieval town in which he finds himself, is filled with shadowy glimpses, sudden uncanny disappearances and a feeling of uncertainty and unease. There’s a telling phrase there too that would have lodged nicely in Lewton's mind: ‘The people did nothing directly. They behaved obliquely’. Which is also, as it happens, a pretty good description of Lewton’s own approach to his remit of producing B-movie horror pictures.

Instead of Universal’s monster-driven approach (which his publicity department, as we shall see, would undoubtedly have preferred and which they went ahead and promoted anyway, regardless of the evidence of the films), Lewton was trying to rethink the area of horror, imbuing it with a little intelligence and class. So, at this juncture, he made some extremely good decisions about his film. He figured, rightly, that instead of a story set in foreign parts, a tale about regular people set in contemporary New York would introduce a disquieting sense of familiarity to proceedings, so he thought afresh about the story and set about scripting an original treatment. After a viewing of Paramount’s 1932 film, Island of Lost Souls, specifically the ‘panther woman’, he realised that any attempt to make up their lead actress to resemble a cat in some way would take them down a very different path to the one he wanted to take, so he rejected that too. Finally, and importantly, he realised that if, as in Blackwood’s tale, he made his lead the man, the audience would always see the woman as a threatening outsider; if on the other hand, he made the woman his lead, and a sympathetic one at that, then the viewers’ feelings would be more engaged. Indeed, in the film it is the ‘plain Americanos’ Oliver and Alice who are the outsiders to the pitiable Irena’s world.

In the film, a woman fears that she is the cursed product of an ancient bloodline and that sexual intimacy or jealousy will unleash the predatory feline that lies within her – a notion that leaves her understanding American beau nonplussed and seeking advice from his workmate Alice, about whom Irena has good cause to be anxious.

The swimming-pool scene in which Alice is menaced by shadows on the walls, the night-time stalking to the rustle of bushes, the ‘Lewton bus’ which unfailingly jolts one alert even when you know it is coming – these are already so deeply embedded in movie lore they require no more discussion here. Another particularly impressive aspect to the film is its hinterland. It’s not directly about fear of the foreigner or incomprehensible ancient ways far removed from new world understanding but this certainly adds piquancy; likewise the treatment of sexual problems which is frank for its time. It is, in the end, all about shadows, real and imagined, in the streets and in the mind. As Lewton once said, ‘audiences will people any patch of prepared darkness with more horror, suspense and frightfulness than the most imaginative writer could dream up.’

Crucially, Cat People made RKO a heap of money and bought Lewton some tolerance for the artistic licence he had already shown, and which he would further indulge in the films which followed. Then a sequel to Cat People was called for and Lewton was given the title The Curse of the Cat People.

A brief aside on titles is worthwhile exploring here. While Cat People was in production, Lewton was given the title for his next project, a title which no doubt made his jaw drop and his shoulders sag, but the title of his next film it was going to be so he might as well make the best of it: I Walked with a Zombie. What he did with this was inspired. He researched voodoo and settled upon a very loose remake of Jane Eyre set in the Caribbean. And the very first lines we hear, as we see an enigmatic couple walking along a beach as the evening sun catches the roll of the waves, are spoken by a pleasant female voice who says with a little laugh, ‘I walked with a zombie – does seem an odd thing to say. Had anyone said that to me a year ago, I’m not at all sure I would have known what a zombie was.’ Boil lanced, ridiculousness addressed, title over and done with, the film goes ahead on its own terms with barely a minute on the clock. Lewton’s next film, The Leopard Man, is not as you might expect about a male equivalent of a cat person but rather a show promoter who owns a melanistic leopard that escapes.

And so to The Curse of the Cat People (which Lewton wanted to call ‘Amy and her Friend’; he didn’t get his way). Reprising their roles from the original movie, Kent Smith and Jane Randolph play Oliver and Alice, now married and with a flaxen-haired 6 year-old child, Amy, whose inclination to dream up imaginary playmates leads Oliver to suspect the lingering influence of his first wife, Irena. Then – on a ring thrown to her by a woman from the window of a mysterious dark house – Amy makes a wish for a friend, bringing Irena into her life, and something has to give between child and parents.

In the most passing of ways The Curse of the Cat People does provide some of the requirements for a sequel of the name. There is a ‘curse’ of sorts – in the meaning of a trait that has been passed on to a new generation – though it is entirely benign (it even saves Amy at one point) and leached of any of the connotations of sexual violence that appeared in Cat People; there is a woman who returns from beyond the grave, though as fairy princess and playmate rather than blank-eyed zombie requiring vengeance, and there is also a threatening dark house on the corner with its cranky, mysterious inhabitants. If we discount an early shot of boys playing at machine-gunning a black cat on a branch – something that sits badly with the rest of the film and which was added at the studio's insistence – there is barely a cat in the film. (Alas, the studio also removed a far more meaningful shot of Amy looking at a picture of Sleeping Beauty in a book – a picture that resembles Irena’s costume and helps to further blur the question of whether Irena is entirely imaginary or not.)

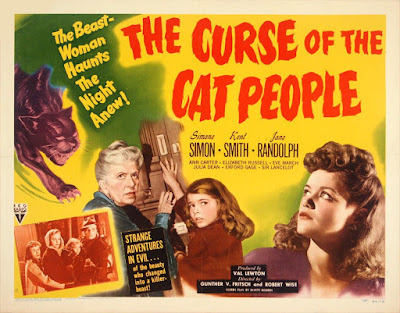

Tantalisingly poised between fantasy and gothic horror, pointed with references to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Unseen Playmate and Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and dabbed with subtle touches of shadowy darkness, The Curse of the Cat People disappointed RKO executives who were after the quick buck-making supernatural thriller that their fevered publicity department went ahead and promoted anyway (‘The Beast-Woman Stalks the Night Anew!’; ‘The Black Menace Creeps Again!’). In giving over its central space to a child’s imagination, what Lewton made was more lasting though.

Central to the film is the performance of the 7 year-old Ann Carter, who is as trusting, wilful, furtive, as lightly contemptuous and as deeply serious as only a 7 year-old can be. Her performance is complemented by genuinely strange elements such as the lithe and haunted Elizabeth Russell slinking around the dark house as the disowned adult daughter, the odd jarring filmic shock and the delicate touches that Lewton always crafted throughout his films.

One scene shows such touches very well. It is Christmas. Amy has gone into the snowy garden to give Irena her gift, and Irena has responded by calling up a magical twinkling of fairy lights. Then Alice calls Amy from the house and, briefly, a shadow passes across Irena’s face that resembles something like jealousy, before it goes as quickly as it came. If you’ve seen Cat People however, it calls up the memory of Irena’s transformation before she attacks Dr Judd, again done with little more than a selective darkening of the image. Irena kisses her and stands to wish her a merry Christmas, and there, by her head is a single icicle glinting from a branch, deliberately placed there I am sure to recall the Dr Judd’s swordstick that pinned Irena’s shoulder in the earlier film. Amy runs inside and for a brief moment, constructed out of nothing more than the shadow on the glass pane of the door and the Christmas tree within, it seems as if there is a weirdly undefined ameobic shape of spreading darkness. Three easily missable but highly crafted effects in 30 seconds of film. Even if you don’t consciously register them, they aid the general atmosphere.

Lewton’s films are sprinkled with such effects. In The Leopard Man, they can so brief as to be practically subliminal: a shadow of a dancer flitting across a fountain, gone as soon as it’s seen; the reflected ripple of water from under a bridge; a woman’s shadow briefly separating from herself in a night-time street as she passes a trash can; the subdued squeal of an organ note that takes half a minute to fade out, just present enough to set nerves on edge as the wind starts to rustle the trees.

As I have mentioned, these films are all about shadows. The previous year, Hitchcock had made a film noir in the bright light of day, Shadow of a Doubt. In The Curse of the Cat People, Lewton showed similarly threatening shadows, this time of the unseen and unquantifiable, latticing a plain old American shutterboard house, and in doing so cautioned that reason cannot vanquish all.

At a screening of his A Story of Children and Film recently, Mark Cousins implored the audience to watch his film with wide-eyed childish wonder (always good advice). I mention this because The Curse of the Cat People is the end point of a story, one of whose beginnings was the lurid, lycanthropic shock-horror of Universal’s The Wolf Man. This mutated into the psychological subtlety of Cat People which then spawned a film about the power of a child’s imagination. Much like cinema itself, it belongs to the child within us all.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment